Tools

7MP Management and Planning Tools

8QC Traditional Quality Control Tools

Failure Mode, Effects, and Criticality Analysis

Maintainability and Availability

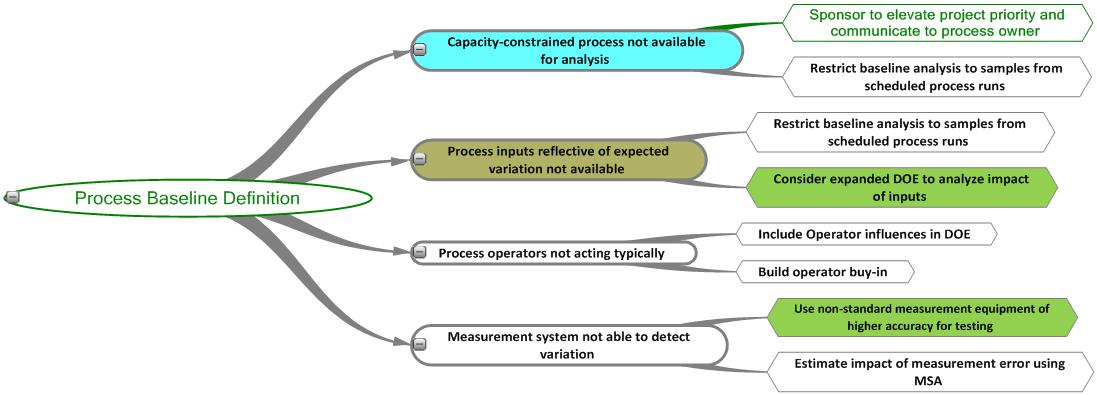

Process Decision Program Charts

Process Decision Program Charts

Process Decision Program Charts are used to delineate the required steps to complete a process, anticipate any problems that might arise in the steps, and map out a way of counteracting the problems. With process decision program charts, you are prepared for any difficulties before they occur. A properly thought out PDPC means that no task is left undone and no unanticipated problem arises.

When to Use

As with any of the Seven Management and Planning Tools, it is important to have the right input into a PDPC. Those contributing to the creation of the chart should have a broad overview of the project, so that all steps are included, and experience with the tasks or with related tasks, so that they know what kind of problems are likely to occur.

The chart begins with a goal, placed at the top or left of the workspace. Branching off from the goal are the various steps that need to be done to achieve this goal. If necessary, there may be a second level of subsidiary tasks under this first level. These steps should not be overly specific, so as to avoid cluttering the chart. (If your goal is to delineate very specific tasks from one large project, you are better off using a tree diagram Now try to think of any problems that might arise in the execution of each process step. Each step should be examined independently. The point of this process is to confront problems which otherwise might not have been addressed. Forcing yourself to try to anticipate problems before they occur may make you think of something you otherwise would not have even dreamed of. Additionally, this process allows people to mention points that they may find troublesome, without feeling like they are being unduly negative. Once you have thought of the problems, the next step is to think of a measure that would counteract this problem. You may think of more than one countermeasure and later decide which solution(s) you would actually like to use. For instance, suppose the anticipated problem is resistance to change among manufacturing workers. Your possible counteractive measures could be an incentive program to boost morale, or an education program to inform workers of the need for change. You can then weigh the costs and benefit of each alternative in order to decide on your course of action. Of course, it is much easier to make these decisions in the calm of the planning room, rather than in the heat of the project when you suddenly discover an unanticipated problem.

Learn more about the Quality Improvement principles and tools for process excellence in Six Sigma Demystified (2011, McGraw-Hill) by Paul Keller, or his online Green Belt certification course ($499).